From soup cans to early ‘selfies’: Celebrating 70 years of pop art

With its bright colours and impish humour, it’s almost hard to believe that this year, the pop art movement turns the ripe old age of 70.

It was such an exciting new wave when it first came about in the Fifties and Sixties, unlike anything else that had come before it, turning traditional expectations of fine art on their head.

One of the most popular pop artists, Richard Hamilton, describes the style best: “Pop Art is: Popular (designed for a mass audience), Transient (short-term solution), Expendable (easily forgotten), Low cost, Mass produced, Young (aimed at youth), Witty, Sexy, Gimmicky, Glamorous, Big business.”

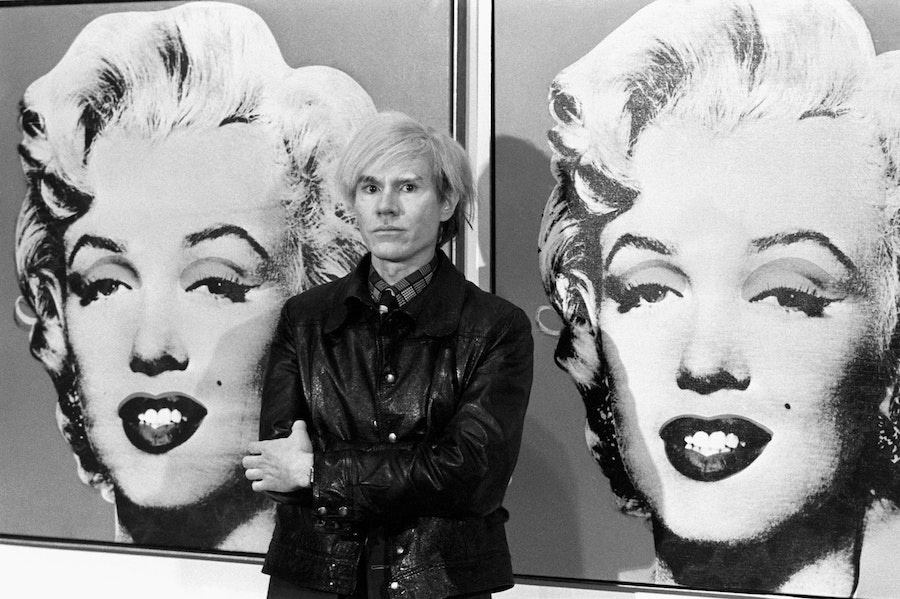

Marilyn 1967 by Andy Warhol is a classic example of pop art, featuring bright colours, an obsession with celebrity and a keen sense of humour

In honour of 2018 marking 70 years since the term ‘pop art’ was first used, we spoke to art historian Dr Laura-Jane Foley, to get the low-down on everyone from Andy Warhol to Richard Hamilton, and understand a bit more about their legacy today…

The difference between British and American pop art

British artist Richard Hamilton’s Singeing London features Mick Jagger, showing the Brits were as obsessed with celebrity as the Americans

There’s no doubt Andy Warhol’s the leading light in the pop art movement. But while his might be the name everyone recognises, Foley really wants British artists to get the recognition they deserve too.

Both countries were “reacting to abstract expressionism”, Foley explains, but “in Britain, it was almost like a pastiche of popular culture in America. We had irony and a sense of satire because we were across the ocean.

“It was very different to pop art in America, which was made by people reflecting on their own culture, so that sense of irony was missing,” she adds.

Warhol regularly used Campbell’s soup in his work

In the US, there was a particular obsession with brands. Art is traditionally seen as an elevated form, unsullied by the realities of modern life. However, pop artists turned this snobbish principle on its head by featuring the most mundane and banal of advertising and brands – everything from Warhol’s Campbell soup cans to his interpretation of the Coca-Cola bottles. This obsession with brands made pop art a more accessible and democratic art form.

British pop art heavily drew upon brands as inspiration too, but it was done more in a way of making fun of consumerism, rather than indulging in it like Warhol was often seen as doing.

Warhol and the cult of celebrity

Michael Jackson was just one of Warhol’s famous subjects

Warhol will forever be remembered for his obsession with celebrity. “He was very aware of how he was positioning his work,” Foley explains. “Think of all the well-known celebrities of the age who are still famous now that he selected – from Mick Jagger to Marilyn Monroe. He was always thinking about how he could position himself to get fame.”

It’s this total self-awareness and desire to be in the spotlight – and stay there – that means Warhol has even been compared to the Kardashians. This isn’t a new idea – back in 2015, i-D wrote an article with the headline: ‘Is Kim Kardashian West the Andy Warhol of our time?’

Self-portrait by Andy Warhol

This isn’t a huge leap. Warhol was obsessed with ‘selfies’ (although they weren’t called that at the time, of course), taking many Polaroids of himself and even transforming them into artworks. Kardashian West is the same – except selfies are a whole lot easier now, thanks to iPhones and apps like Facetune.

Pop art’s legacy

Pop art exhibitions like this 2013 one at London’s Barbican show how mainstream the movement has become

The whole point of pop art was to be controversial and outside of the norm – which is why it’s quite ironic, in some ways, that the likes of Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein are now taught at universities.

“In a sense, maybe they’d be disappointed they’ve become part of the canon,” Foley muses. “They were trying to do something new and different and now they’re part of the curriculum. Artists always start off with ideas of changing and revolutionising things, but then they actually become part of the establishment, and the next generation comes in and tries to change things!”

Artists who have been influenced by the movement

Damien Hirst has worked to become as ubiquitous as Warhol

It’s not just the Kardashians who have similarities with Warhol and pop art’s obsession with the cult of celebrity – there’s a whole generation of artists who are the same.

“It almost looks like Damien Hirst has based his career on Warhol,” says Foley. “It’s like a mirror in that he has great ideas and grand plans, and then he gets someone else to execute them. Hirst is very skillful at manipulating his own persona, and that’s something that Warhol did.”

This idea of an artist manipulating their image has gone global, and Foley adds: “Ai Weiwei is another who I would say knows how to curate his own image and project his own persona.”

The Ai Wei Wei / Andy Warhol show actually made a lot of sense. Wonderful parallels and interaction @TheWarholMuseum pic.twitter.com/P7XkdediNV

— Viewer (@PeripateticMe) July 3, 2016

Foley isn’t the first to draw comparisons between the Chinese artist and Warhol – in 2015, the National Gallery of Victoria in Australia put on a joint exhibition of the two. On the surface, the artists deal with completely different themes – Warhol with 20th century American life and Weiwei with the state of China in the turn of the century – but seeing them together shows that both love to subvert popular culture and are similarly iconoclastic.

Indeed, it’s particularly telling that Weiwei was involved in developing the show – like Warhol, he’s keenly aware of curating his own image.

As Foley notes: “I think this idea of connections between artists are really important.” After all, it’s exhibitions like this that will help keep the pop art movement feeling fresh, and opening it up to new audiences.

Dr Laura Jane Foley is one of the UK’s leading art historians and creator of podcast, My Favourite Work Of Art, which will be available to download from Apple Podcasts on August 21 at acast.com/myfavouriteworkofart.

The Press Association

Latest posts by The Press Association (see all)

- Maple Cinnamon Granola - January 8, 2025

- 8 things your feet can tell you about your health - January 8, 2025

- 9 ways to look after your emotional health better in 2025 - January 7, 2025

- EastEnders fans to vote on storyline for the first time in 40th anniversary week - January 7, 2025

- Aldi beats rival Lidl as cheapest supermarket of 2024 - January 6, 2025