Acting that speaks louder than words: The enduring appeal of silent movies

On one level, it’s odd that silent movies are still finding an audience. Grainy graphics, static camerawork and, well, no dialogue – viewers could be excused for preferring conversation and CGI.

But for those willing to look beyond the terrible tech, silent movies still have a lot to offer.

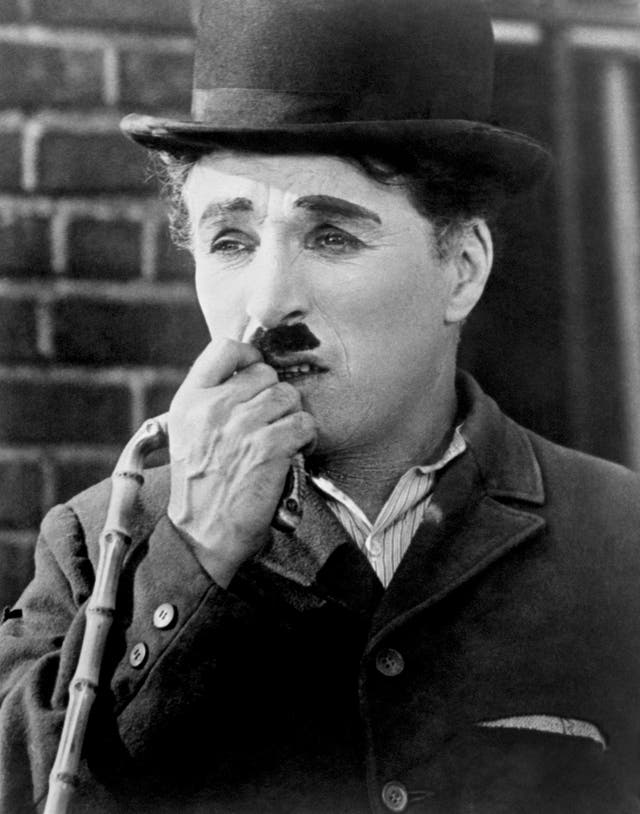

Whether it be Laurel & Hardy dropping a piano down a staircase, Greta Garbo smouldering her way through an evening of intense Hollywood melodrama or Charlie Chaplin’s famously pained smile, silent movies still present compelling narratives – just with a slightly different language.

Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy in their classic garb

With Stan & Ollie, the new film inspired by the iconic comedy duo, barely a month old, here, we take a look back through the unique methods of storytelling necessitated by mute movies and the strange, scandalous world of silent-era Hollywood, where stars were expected to be as voiceless as their characters…

A different style of storytelling

First, let’s dispel a few myths: You have to go back a very long way for silent movies to actually be silent. The ‘moving pictures’ of the 1910s and 1920s did not have synchronised audio, but did come with musical tracks or accompaniment by house bands. When characters needed to call upon words, they would be flashed up on a card, generally one short sentence at a time.

There is a universality in silent movies that is lost the moment someone opens their mouth. Charlie Chaplin’s iconic character ‘The Tramp’ is cinema’s supreme Everyman – a small, voiceless man in ill-fitting trousers, struggling to stay afloat in a difficult world. Endearing but serious, hapless without being pathetic, The Tramp has no accent, no creed, no opinions of any kind, and serves to embody the viewer as much as entertain them.

Charlie Chaplin

Widely considered the inventor of the montage, Soviet director Sergei Eisenstein goes a step further. His 1925 film Battleship Potemkin has no central character, and communicates instead through sweeping set pieces, featuring thronging crowds and a triumphalist score. Searingly emotive and self-evidently communist, Eisenstein’s films articulate the anguish of the many, by silencing the voices of the few.

At the lighter end of the scale, Laurel & Hardy, Harold Lloyd, and Buster Keaton were writing the rule book on physical comedy, imbuing the slightest of movements with significance. Keaton – nicknamed ‘The Great Stone Face’ for an heroically deadpan delivery – could famously switch from laughter to grief in the space of a single stare.

Silent stories could tell complex, evocative narratives – but they did so with expansive gestures, dramatic facial expressions, and carefully choreographed body language.

A (very) brief history of silent film

The first ever movies were monochrome, mute, and only a few seconds long. There’s any number of answers to the question of who invented film, so we’ll leave that one to Google, but we can say that the first commercially available film was screened by the Lumière brothers in the Grand Cafe in Paris in 1895.

In modern parlance, the film – a 15-minute mishmash of narrative shorts – was a sleeper hit. The grand opening garnered few column inches and what reviews there were, were sniffy, but word of mouth slowly built up queues that stretched down the street.

Buster Keaton was said to have a face like a slab of granite (PA)

Success breeds imitation, and before long, films were touring fairgrounds, restaurants and music halls – anywhere with the space to set up a screen and an abundance of paying public. National cinema associations sprang up across Europe and America, and cinema soon developed into one of the Western world’s premier entertainments.

1915 saw the release of The Birth Of A Nation, a film that still ties critics in knots and puts modern Hollywood controversies to shame. An enduring masterpiece, DW Griffith’s three-hour epic redefined the boundaries of narrative cinema, showcased unprecedented levels of technical achievement, and was the highest-grossing film ever until Gone With The Wind came along more than two decades later.

After a heyday in the early-1920s – and the emergence of the first generation of modern movie stars – 1927’s The Jazz Singer brought conversation to the silver screen. Silents stuck for some years after – Chaplin famously preferred them – but by the 1930s, most movies had learned to talk.

Jean Dujardin talking in technicolor

Perhaps ironically, we now watch more films about silent films than we do silent films themselves. As early as 1950, American classic Sunset Boulevard tracked the descent into madness of a fading silent film icon, unable to accept that the onset of the ‘talkies’ had rendered her obsolete.

More recently, The Artist served as a loving eulogy to silent cinema, and anyone who watched the 2012 Academy Awards can confirm the lack of talking did not put off critics or audiences.

In 2016, it was followed by classic Coen Brothers farce, Hail, Caesar! Though set in the 1950s, it followed real-life fixer Eddie Mannix, who became MGM’s general manager in the 1920s. The movie’s Mannix sweet-talks journalists, investigates missing people, and generally tries to make everything OK. The real Eddie Mannix was reportedly a great deal nastier.

Notes on a scandal

In silent-era Hollywood, off-camera truth was often stranger than on-camera fiction, and superstars needed to have perfect families, ever-present smiles and impenetrable pasts.

It became easier for studios to hide their stars than excuse them, and many of the hush-hush cover-ups have passed into Hollywood folklore. Mannix apparently left a trail of forced abortions, sham marriages, and possibly even a few unsolved murders in his wake.

Swedish superstar Greta Garbo

Sexuality, particularly female sexuality, was off the menu throughout the industry, despite there being rather a lot of it around. Enduring megastar Marlene Dietrich lived her lie so effectively that even now, her reportedly voracious lesbian appetite is not particularly widely known. Partners were rumoured to include Edith Piaf, a young Greta Garbo and possibly even Marilyn Monroe.

Katharine Hepburn, Spencer Tracy, Barbara Stanwyck – homosexuality rumours swirled about most of the Hollywood A-list, but it was a time when powerful studios seemed keen to keep them just that.

They maintained an uneasy relationship with the gossip columnists, whose pens could make or break promising young careers. Who knows how many scandals have been lost to the annals of history, buried by pugnacious fixers a little too good at their jobs. The rise of the film star didn’t just shape the modern film, it laid the blueprint for modern celebrity.

When scandals did break, they really broke. Take the tale of Clara Bow, the original ‘It girl’, whose apparent sexual proclivities were laid bare by the Coast Reporter in 1931.

Clara Bow – a tragic heroine for the Hollywood age (PA)

“Crisis-a-day-Clara” was known throughout Hollywood for a prodigious number of affairs and a steadfast refusal to be prim and proper, so was clearly considered a soft target.

Her theatrical response would have stolen the show at any talkie: “They yell at me to be dignified. But what are the dignified people like? They are frightful snobs. I’m a curiosity in Hollywood – a big freak, because I’m myself!”

The Press Association

Latest posts by The Press Association (see all)

- Sir Rod Stewart ‘proud and ready’ to play legends slot at Glastonbury 2025 - November 26, 2024

- Barbara Taylor Bradford, the ‘grand dame of blockbusters’, dies aged 91 - November 25, 2024

- How to add scent to your natural Christmas decorations and wreaths - November 25, 2024

- Chocolate and ginger biscotti recipe - November 24, 2024

- 5 new books to read this week - November 23, 2024